Archief

Titel

1.04.21 Inventaris van de archieven van de Nederlandse Factorij in Japan te Hirado [1609-1641] en te Deshima, [1641-1860], 1609-1860

Auteur

M.P.H. RoessinghVersie

23-09-2024

Copyright

Nationaal Archief, Den Haag

1964 cc0Beschrijving van het archief

Naam archiefblok

Nederlandse Factorij in Japan Nederlandse Factorij Japan

Periodisering

oudste stuk - jongste stuk: 1609-1860

Archiefbloknummer

170Omvang

1973 inventarisnummer(s) 39,90 meterTaal van het archiefmateriaal

Het merendeel der stukken is in het, een aantal stukken zijn in heten het.

Nederlands

Japans

Engels

Soort archiefmateriaal

Normale geschreven en gedrukte teksten. De Nederlandstalige stukken van vóór ca. 1700 zijn geschreven in het gotische cursiefschrift, met name in de oud-Hollandse klerkencursief.Archiefdienst

Nationaal ArchiefLocatie

Den HaagArchiefvormers

Factorij Hirado Factorij Hirado DeshimaSamenvatting van de inhoud van het archief

Contains records dating from the period 1609-1842: originating from the opperhoofd (chief-factor) and council (proceedings, diaries, correspondence, legal records), from the warehouse custodian annex bookkeeper annex scribe (notarial deeds, estate papers), from the Society of private trade (proceedings, correspondence, accounts), manuscripts of G.F. Meylan concerning Japan; and from the period 1842-1860: originating from the opperhoofd and council, from the warehouse custodian annex bookkeeper annex scribe and from J.H. Donker Curtius, envoy to the court in Edo.Archiefvorming

Geschiedenis van de archiefvormer

1. The establishment of the Dutch factory in Japan.

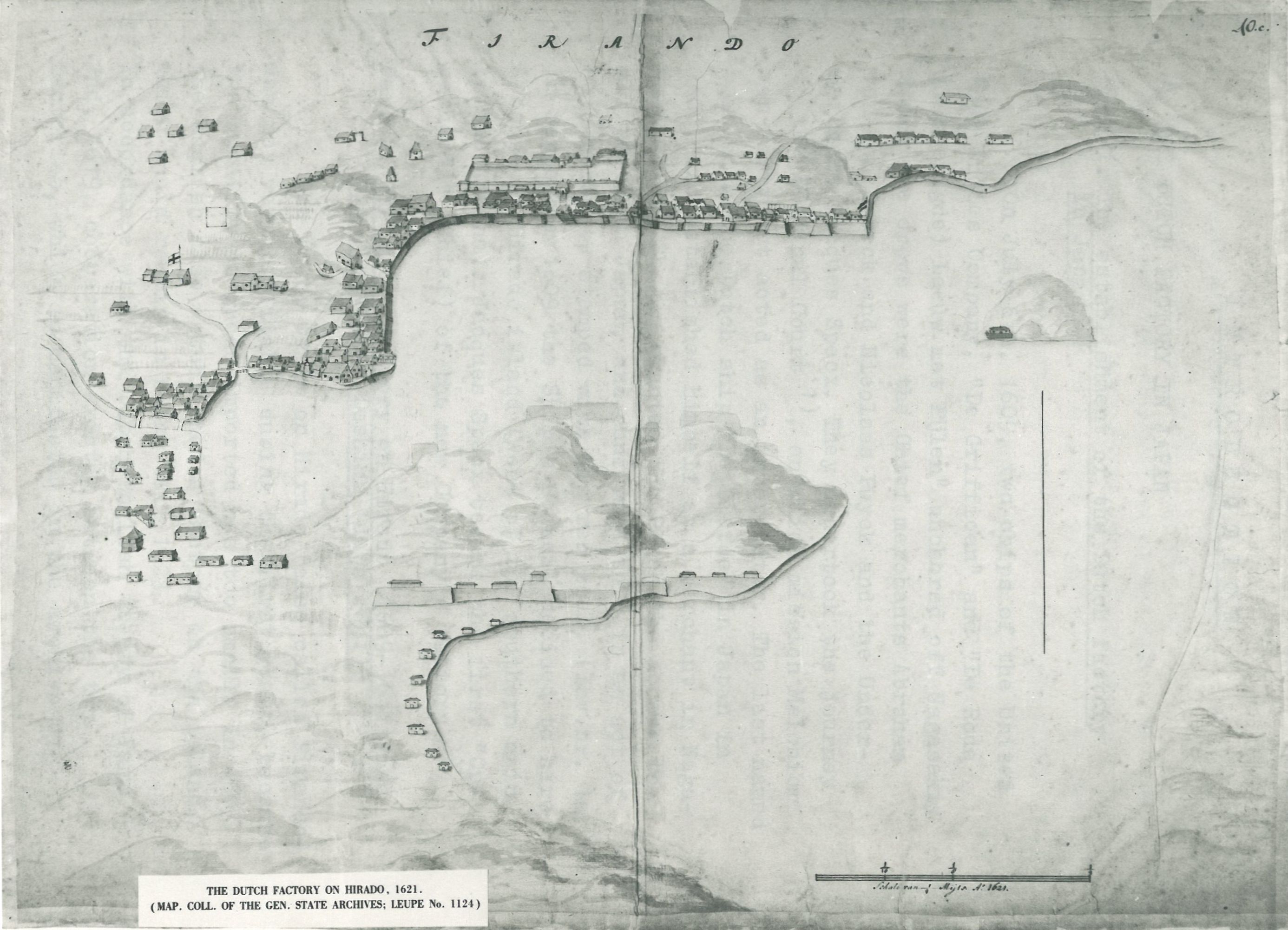

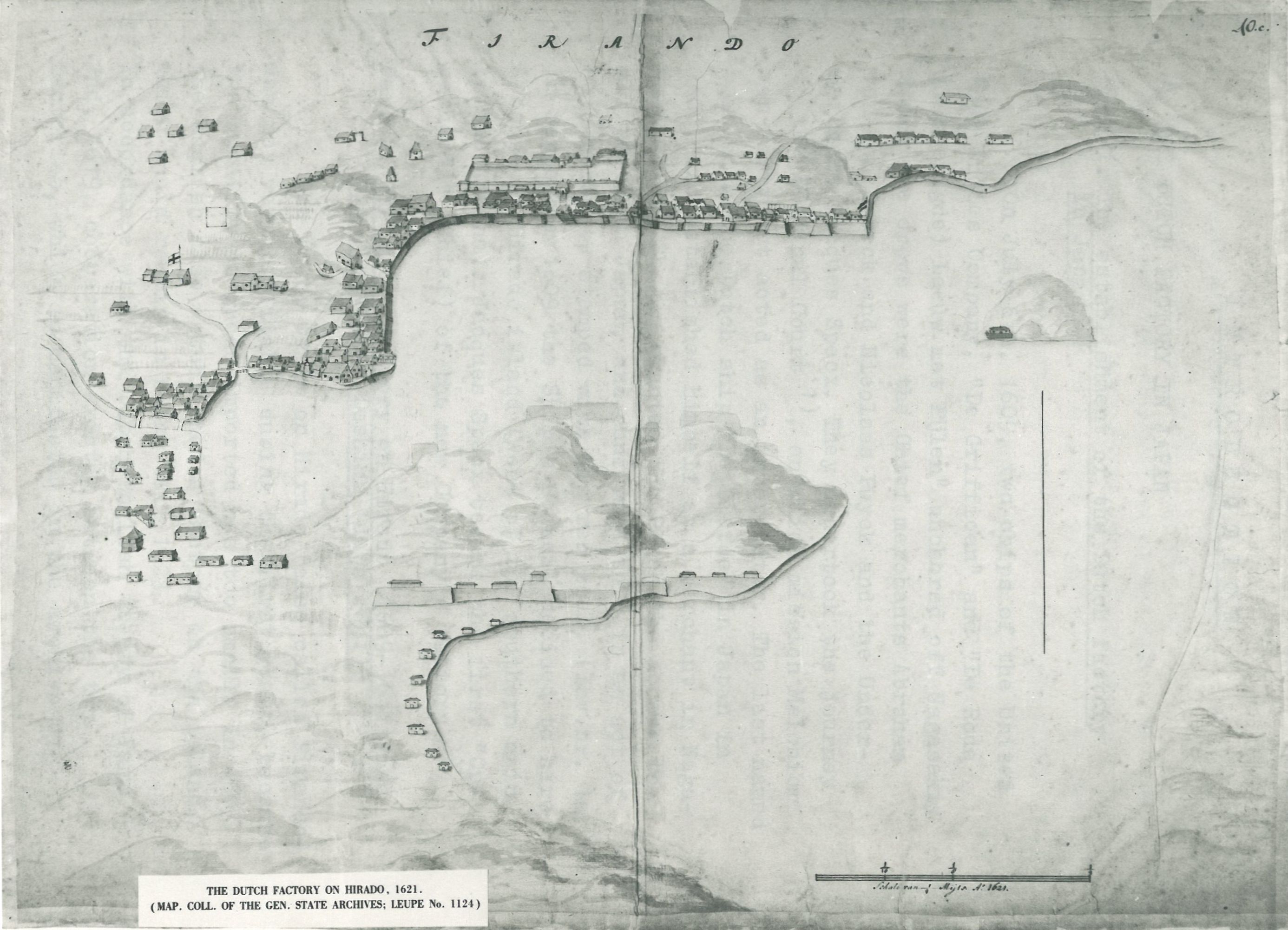

On July 6th, 1609, two ships of the United East Indies Company, "De Griffioen" and "De Rode (Vereenigde) Leeuw met Pijlen" anchored off Hirado. Among the crews were the Chief merchants Abraham van den Broeck and Nicolaas Puyck and the Under-merchant Jacques Specx. They undertook the journey to the Shogunal Court ( 'Shogun': 'Commander-in-Chief'; in fact: Military Governor of the Empire of Japan. Cf. Boxer, ) Jan Compagnie ( , p. 189-190, Feenstra Kuiper, p. 328-330, and Sansom, I-III, glossaries and indexes, for the translation and explanation of Japanese words. ) , on wich mission Melchior van Santvoort acted as an interpreter. The last named came with the Dutch ship "De Liefde" in Japan in 1600, and established himself as a merchant in Nagasaki. ( Cf. for the period 1600-1609: Wieder, vol. III. About the archival sources relating to the ships: V.R.O.A. ) 1916, ( p. 17. ) The Shogun granted the Dutch the access to all ports in Japan, and confirmed this in an act of safe-conduct, stamped with his red seal. ( See inv.nr. 1a. ) In September 1609 the Ship's Council decided to hire a house on Hirado island (west of the southern main island Kiushu). Jacques Specx became the first "Opperhoofd" (Chief) of the new Company's factory. ( Nachod. p. 110-115. )2. The Dutch factory on Hirado (1609-1641) and the removal to Deshima (June 1641).

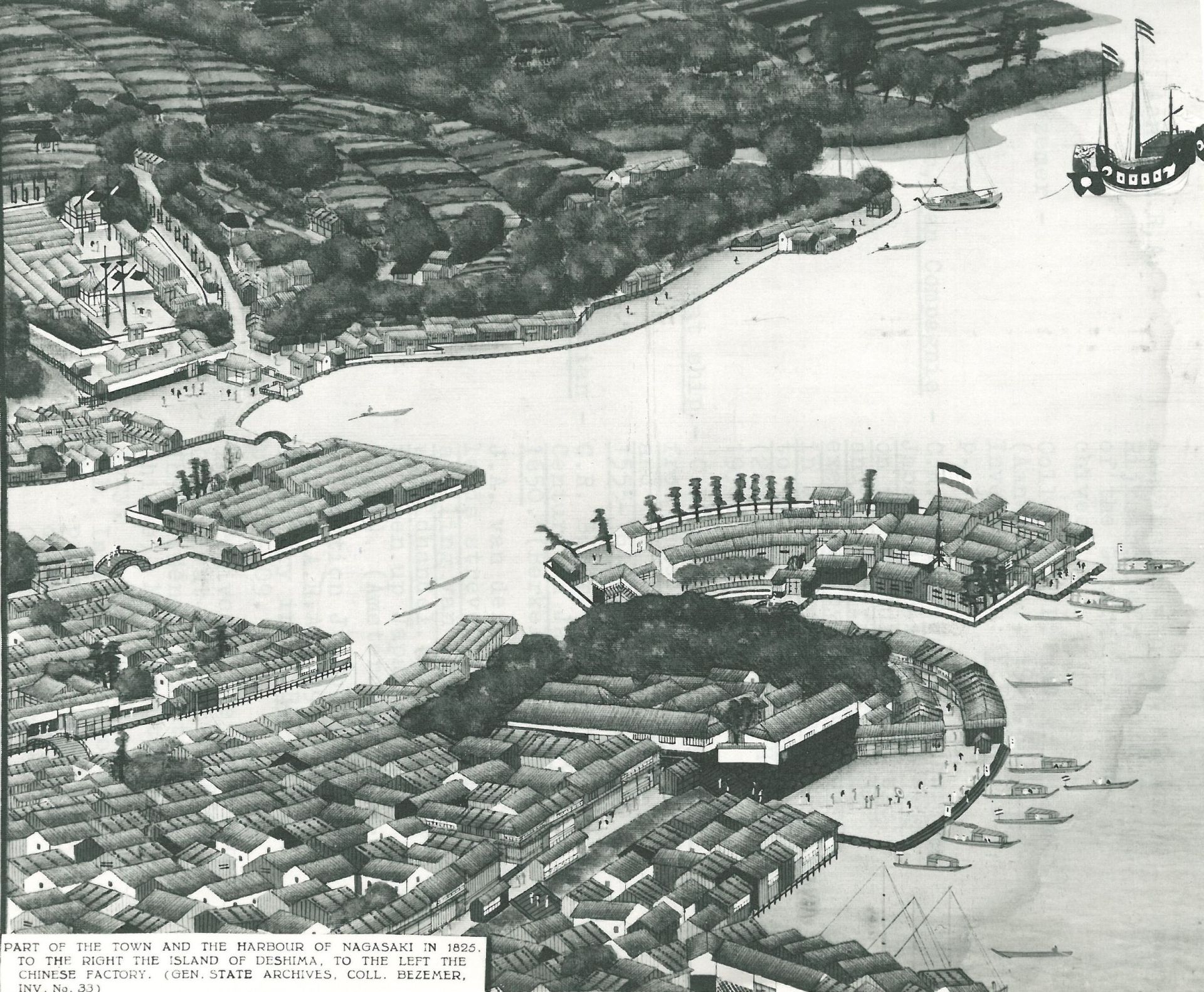

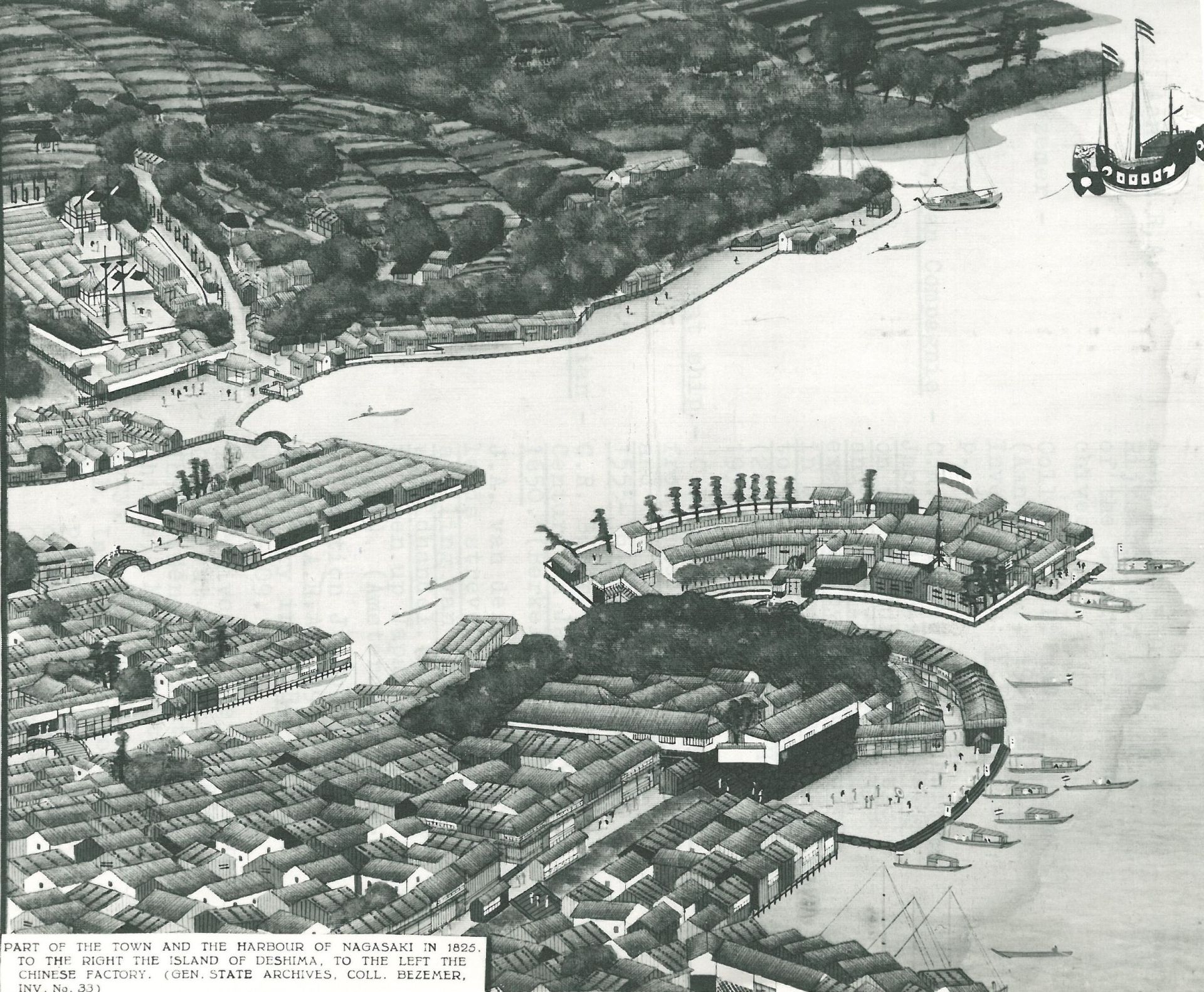

The Dutch trade on Hirado (also called Firando) was not very profitable during the first years, because the quantity of goods imported was too small. In 1613 the English also established a factory on the island, wich would remain in being till 1623. In accordance with the Dutch-English treaty of June 2nd, 1619, coöperation existed between the two factories, wich is manifested in the archive by resolutions of the combined ship's Councils and both Chiefs. ( See inv.nr. 3. ) Although the Shogun in 1617 restricted the overseas trade to the harbours of Nagasaki and Hirado, the Dutch received a new act of safe-conduct on their journey to the Shogunal Court of that year, wich passport guaranteed them free entrance in all Japanese ports. ( See inv.nr. 1b. The much-used term 'trade-passport' for these documents is thus - strictly taken - incorrect. Cf. Nachod, p. 170-171. See also inv.nr. 2, which letter has indeed the character of a grant of free trade. ) The efforts of both the English and the Dutch to capture the richly-laden Portuguese carracks and Chinese junks, sailing from and to Nagasaki, led to a sharp reprimand of the Japanese Government in 1621. ( Corpus, I, p. 172-174. ) The Shogunal Government, on the other hand, became more and more opposed to the Portuguese, because of their missionary activity. The Shogun believed that the existing order in Japan was endangered by the expanding Christian religion. After the revolt of Japanese Christians on the promontory of Shimabara (east of Nagasaki) in 1637 and 1638 the Portuguese were duly expelled from the Empire (1639), the Dutch had to demolish their newly-built wharehouse on Hirado (1640) and in 1641 the removal of the factory to Deshima was ordered. The Portuguese had been confined on this artificially constructed islet in the harbour of Nagisaki from 1636 to 1639. It was built in 1634 and 1635 through the contributions of 25 local merchants. ( Goodman, p.14; Boxer, ) The great ship ( , p. 146 ) The Dutch factory remained here until theclosing-down in 1860. From 1639 to 1854 the Dutch were the only Europeans permitted to enter japan. The Spanish had been expelled already in 1624: the English abandoned their factory voluntarily in 1623 and were not admitted again until 1854, although they tried several times to reopen the trade. Together with the Chinese, the Dutch provided for the overseas trade of Japan, because in 1636 the Shogun finally forbade the Japanese to go abroad, after a series of restricting measures in the years 1633-1636. ( Cf. Boxer, ) The Christian Century ( , especially p. 372. For the sake of completeness it should be mentioned, that Siamese envoys and trade ships occasionally visited Japan during the period of seclusion, and that there was trade with Korea through the Tsushima Island (North of Kiushu). Cf. Iwao, p. 1 and passim. ) The removal to Deshima took place in June 1641. A short time after the establishment, in August 1641, the Chief of the factory received a letter from the Governor of Nagasaki, in which were promulgated a number of very onerous regulations and restrictions concerning the residence of the Dutch on the island. ( Corpus, I, p. 356-358. ) These and others regulations remained in force practically unaltered until the closing-down of the facory.

The Dutch trade on Hirado (also called Firando) was not very profitable during the first years, because the quantity of goods imported was too small. In 1613 the English also established a factory on the island, wich would remain in being till 1623. In accordance with the Dutch-English treaty of June 2nd, 1619, coöperation existed between the two factories, wich is manifested in the archive by resolutions of the combined ship's Councils and both Chiefs. ( See inv.nr. 3. ) Although the Shogun in 1617 restricted the overseas trade to the harbours of Nagasaki and Hirado, the Dutch received a new act of safe-conduct on their journey to the Shogunal Court of that year, wich passport guaranteed them free entrance in all Japanese ports. ( See inv.nr. 1b. The much-used term 'trade-passport' for these documents is thus - strictly taken - incorrect. Cf. Nachod, p. 170-171. See also inv.nr. 2, which letter has indeed the character of a grant of free trade. ) The efforts of both the English and the Dutch to capture the richly-laden Portuguese carracks and Chinese junks, sailing from and to Nagasaki, led to a sharp reprimand of the Japanese Government in 1621. ( Corpus, I, p. 172-174. ) The Shogunal Government, on the other hand, became more and more opposed to the Portuguese, because of their missionary activity. The Shogun believed that the existing order in Japan was endangered by the expanding Christian religion. After the revolt of Japanese Christians on the promontory of Shimabara (east of Nagasaki) in 1637 and 1638 the Portuguese were duly expelled from the Empire (1639), the Dutch had to demolish their newly-built wharehouse on Hirado (1640) and in 1641 the removal of the factory to Deshima was ordered. The Portuguese had been confined on this artificially constructed islet in the harbour of Nagisaki from 1636 to 1639. It was built in 1634 and 1635 through the contributions of 25 local merchants. ( Goodman, p.14; Boxer, ) The great ship ( , p. 146 ) The Dutch factory remained here until theclosing-down in 1860. From 1639 to 1854 the Dutch were the only Europeans permitted to enter japan. The Spanish had been expelled already in 1624: the English abandoned their factory voluntarily in 1623 and were not admitted again until 1854, although they tried several times to reopen the trade. Together with the Chinese, the Dutch provided for the overseas trade of Japan, because in 1636 the Shogun finally forbade the Japanese to go abroad, after a series of restricting measures in the years 1633-1636. ( Cf. Boxer, ) The Christian Century ( , especially p. 372. For the sake of completeness it should be mentioned, that Siamese envoys and trade ships occasionally visited Japan during the period of seclusion, and that there was trade with Korea through the Tsushima Island (North of Kiushu). Cf. Iwao, p. 1 and passim. ) The removal to Deshima took place in June 1641. A short time after the establishment, in August 1641, the Chief of the factory received a letter from the Governor of Nagasaki, in which were promulgated a number of very onerous regulations and restrictions concerning the residence of the Dutch on the island. ( Corpus, I, p. 356-358. ) These and others regulations remained in force practically unaltered until the closing-down of the facory.3. The Government of Japan.

At the end of the sixteenth century the daimyo ( 'Daimyo': 'Great name'; the head of a clan with a minimum revenue of 10.000 koku (bales) of rice. ) of Japan were involved in a struggle for power, from which in 1600 Ieyasu, of the House of Tokugawa, emerged victorious after the battle of Sekigahara. He recieved the title 'Shogun' from the Emperor and made Edo (Dutch:"Jedo"; the later Tokyo) his capital. The Emperor ('Mikado'; 'Tenno') remained in Miako (the later Kyoto). He did not have any governing power but must be seen as a symbol of the continuity of the Shinto-religion. The relation between the Emperor and the Shogun can be compared more or less with that between the Merovingian King and his Majordomus. ( Nachod, p. 121. 'Mikado', 'Tenno', 'Lord of Heaven'. When the Dutch spoke about "de Keyser" ("the Emperor"), they meant the Shogun. The Tenno they called "Geestelijcke Keyser" ("Clerical Emperor") or 'Dairi'. This word means court or palace. ) A number of important provinces and cities, among which the five big cities Edo, Miako, Osaka, Sakai and Nagasaki, stood under direct control of the so-called 'Bakufu'. ( 'Bakufu': 'Tent-government'; with 'tent' is meant the curtain that screened off the Shogun on the battlefield. ) The most important government council was the Go Roju or Council of Five Elders (Dutch; "Ordinaire Rijksraad"), with 4 or 5 members. The other cities and the rest of the country were governed by officials, arising from the daimyo class. In the course of years these functions became hereditary. The daimyo - vassals of the Shogun - were obliged to military service, the yielding of gifts and the yearly alternating residence in Edo. A number of 'metsuke' (secret police; "dwarskijckers" in the language of the Company) controlled both the feudal lords and the officials.This rigid system of government could be maintained for centuries because the closed-country police repelled all foreighn influences.4. The government of Nagasaki. The relations between the Japanese Authorities and the Dutch on Deshima.

The port of Nagasaki, where from 1641 onwards all foreign traffic wasconcentrated, stood, as has been previously said, under direct control of theBakufu. ( Cf. for the following: Feenstra Kuiper, p. 87 seq.; Goodman p. 44 seq., Boxer, ) Jan Compagnie ( , Ch. IV. ) The central government was represented by two governors, 'Bugyo' ( 'Bugyo': 'Bringer of gifts': magistrate appointed by the central government. ) , who resided alternately in the capital. The Dutch called them "Gouverneurs", whilst they had various names for the subordinate officials: "Bongiozen" or "Banjozen" (derived from the word 'Banjo-shu'). There was also a council of town elders, 'Toshiyorishu', 'Machi-doshiyori', proceeding from the local landowners. (Dutch: "Stadsburgemeesters"). Every member in turn was at the head of affairs during one year. Jap.:'Nemban'; Dutch: "Opperburgemeester" or "Rapporteur Burgemeester"). The town of Nagasaki was divided into quarters, each quarter controlled by an'Otona'. Deshima constituted a seperated quarter under the guidance of threeOtona, who alternated every day at noon. The interpreters were formed into a sort of guild or college ("het Collegie" they call themselves for short in their translations) with a maximum strength of 150, seniors and apprentices together. "Though their positions dated from the Dutch factory at Hirado, their systematic ranks seen to have emerged in the Nagasaki-Deshima era... Theinterpreters combined the jobs of linguist, commercial agent and spy". ( Goodman, p.47. ) After 1695, seven senior interpreters under the leadership of a 'metsuke' formed a College of Head Interpreters. (Dutch : "Collegie van Oppertolken"). These eight persons signed and stamped the engrossments and translations of nearly all documents that were exchanged between the Dutch and the Japanese authorities. Apart from these "Gouverneurs, banjozen, burgemeesters, opper- en ondertolken, ottenaas, ende dwarskijckers" the Dutch had to deal with the purveyors of the victuals for the factory ( The so-called "compradoors". The word is derived from the Portuguese "comprador": "buyer". ) , the cooks,servants, fireguard, gate-keepers, coolies etc. All were paid or given gifts bythe Company, wich thus provided a living for an important part of the inhabitants of Nagasaki. ( Cf. Nachod, p. 421. ) All contact with Japanese officials must be maintained through the interpreters. The majority of the Company's servants thus acquired only a scanty knowledge of the Japanese language, wich was further impeded on the part of the Opperhoofden by their annual change in office. ( See the next paragraph. ) Moreover, the Bakufu generally thwarted the efforts of Dutch and Japanese alike to establish a closer contact outside the commercial sphere. Therefore the Governors-General at Batavia mostly used Chinese language in their letters to the Shogun, the Imperial Council or the Nagasaki Governors. ( Cf. inv.nrs. 638-639. ) In this way there was greater certainty that the contents would reach their destination in the original form and meaning, not being mistranslated by the interpreters. In the 17th century the interpreters often had an insufficient command of the Dutch language, which caused much trouble and annoyance on both sides. Of course, the total absence of dictionaries ond other expedients made the task of the interpreters a difficult one. After about 1670, things change for the better: on 15 December 1670 the interpreters are recorded to be exercising in Dutch handwriting and in 1671 the Governor orders the intruction of interpreters on Deshima. ( Goodman, p. 50. ) The daily entrance of 9 November 1673 contains the following passage: "The interpreters come to inform us that the Governor has decided and ordered that a certain Japanese boy, about ten or twelve years old, will come here daily on the island, in order to learn Dutch from one of the Company's servants, as likewise to be taught how to read and write the same." ( Inv.nr. 87, fol. 4-5. Engl. translated. from Boxer, ) Jan Compagnie ( , p. 60. )

5. The personnel of the factory.

By a regulation of 7 June 1678, Governor-General and Council decided that the personnel of the factory should consist of a merchant, a second merchant, two or three undermerchants and fourteen or fifteen assistants (a surgeon and his assistant included). Plakaatboek, III ( , p. 5. ) The merchant bore the title of "Opperhoofd" (Chief); he held a seat in the Council of Justice at Batavia every period when he was out of office. ( Regulation G.-G. and Council, 9 July 1672. ) Plakaatboek, II ( , p. 558-559. The Japanese called the Opperhoofd 'Oranda Kapitan', i.e. Dutch Captain. ("Hollandse Kapitein" in the translation of the interpreters). ) In 1640 the Japanese demanded that a new Opperhoofd should be appointed every year. This gave rise to a system of rotation, by which every Opperhoofd held the highest post of the factory three to four times. In 1790, the Director-General of the trade, Johannes Siberg, succeeded in obtaining approval for a longer stay. The Council of the factory consisted of the Opperhoofd, the second merchants and the undermerchants. Since 1764, the scribe (at the same time bookkeeper and wharehouse custodian) attended the meetings of the Council and also signed the resolutions. ( Resolution of G.-G. and Council, 16 April 1764; ) Realia, II ( , p. 46. ) The scribe had the power to pass notarial and secretarial instruments and to confirm sworn testimonies. Initially, he had the rank of an assistant, later on - as wharehouse custodian-book-keeper-scribe - of an undermerchant. After the dissolution of the Company in February 1796, no great changes occurred regarding the number, the task and the competence of the inhabitants of Deshima. Sometime between 1796 and 1816, the Council, taking resolutions independently within the limits of their instructions from G.-G. and Council, dissapeared; after 1816, the Opperhoofd decided alone. The title "Opperhoofd" changed into "Gouvernmentskommissaris voor Japan" (Government Commissioner for Japan) in 1855 and since 1859 the representative of the Netherlands was also Consul-General for Japan and Political Agent of the Netherlands in Japan. The last Opperhoofd, J.H. Donker Curtius, who bore each of these titles in turn, signed the first treaty between the Netherlands and Japan in 1856. ( Wijnaendts van Resandt, p. 177-178; in this book is given a name-list of the Opperhoofden of the 17th and 18th centuries with biographical notes, not without mistakes. Cf. also the Appendix of this inventory. Cf. van Kleffens, annex III, for the text of the treaty of 30 January 1856. )6. The journeys to the Shogunal Court.

At their arrival in Japan the Dutch obtained the privilege to be received in audience by the Shogun every year. (This was never granted to the Chinese). On the occasion of the "hofreis" (journey to the (Shogunal) Court) the most important government authorities were honoured with gifts. The privilege became an onerous duty in the course of years, on account of the high expenditure and the burdensome journey, wich was relieved so far in 1790, that the journey only needed to be made every fourth year. The gifts, however, must be brought every year. When the Opperhoofd did not make the journey himself, these gifts were carried to Edo by a group of interpreters. In 1720 and 1783 no journey was made, because no ships arrived from Batavia in the previous year and therefore no gifts could be made. The number of journeys from 1633 (the first year of which a daily journal of the factory is preserved) to 1850 amounts to 186.

Until 1649 the scribe accompanied the Opperhoofd to the Edo Court; from that year on the surgeon of the factory always joined the travelling party. This was frequently consulted by the physicians of the court. The small party of Dutchmen was accompanied by a host of Japanese officials, interpreters, servants, outriders, porters of the Opperhoofd's 'norimono' (palanquin), etc. The Opperhoofd had the rank and status of a daimyo during the whole journey (indispensable for a person recieved in audience by the Shogun) and was treated as such on his way to the capital. The expedition took 12 to 13 weeks in all during the first half of the 17th century from the beginning of December till the beginning of March, after about 1660 from the middle of February till the end of May. A few days after the arrival in Edo the Shogun granted an audience, followed by a more informal meeting and several visits to members of the Bakufu. After a sojourn of 2 or 3 weeks the visitors set out on the journey back, supplied with the traditional present made in return: thirty silk kimono's ("Keyserlijcke rokken"); (Imperial Gowns). The expedition went partly by land (Nagasaki - Strait of Shimonoseki; -Osaka - Edo), partly by sea (Strait of Shimonoseki - Osaka). The total distance covered was over 2000 kilometers.

7. The managing of business at the factory.

The yearly routine at the factory was determined by the arrival and the departure of ships. At the end of June two or three ships left from Batavia and sailed with the south-western monsoon to Japan in four or five weeks. This was the case at least in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the 17th century the ships often sailed via Siam, Tonking etc. to take on trade-goods there. With these ships the new Opperhoofd also came to Japan. Therefore two Opperhoofden were at the factory during the trade-season, from about 15 August till the end of October. At the end of October or the middle of November the accounts were closed, the resigning Opperhoofd instructed his successor ( A number of these so-called "Memories van overgave" ('Memoirs of surrender', i.e. to the successor in office) have been preserved in inv.nrs. 31-45. Cf. also inv.nr. 659. ) , and the ships left for Batavia with the north-eastern monsoon. With the Opperhoofd, the second merchant and some of the undermerchants and assistants also returned to Batavia, as they only were needed at the factory during the busy trade-season. During the voyage the report on trade since October of the past year was written or finished. Around New Year one arrived at Batavia. The voyage back often took more time than the outward voyage, because one had to reckon not only with the monsoon but also with the Japanese prescriptions concerning the date of departure. On Deshima, in the meantime, preparations were made for the journey to Edo (Nov.- Febr.); during that trip (Febr.- May) an undermerchant took the place of the Opperhoofd. From May the middle of August the factory was put in readiness for the next trade-season; sometimes a remnantsale was held. In the 1840's the factory more or less changed from a trade-station into a sort of pre-diplomatic residence. ( Cf. van Kleffens, p. 22-23. ) Trade was at that time of minor importance, the more so when compared with that of the previous centuries. For the Netherlands, the factory became a means to procure the opening of Japan for foreign nations; for Japan, it was - as it had been since 1639 - the only channel through which filtered the news from the Western world. ( Cf. e.g. inv.nrs. 1749-1758. ) The letter of King William II to the Shogun, sent by way of H.M.S. "Palembang" in 1844, in wich the King gave the assurance that the opening of Japan would be beneficial for Japan and the outer world alike, exemplifies the changed attitude on the part of the Dutch. ( The answer of the Shogun accompanied by some costly presents, was cordial but negative; cf. inv.nrs. 1707-1716. ) In 1847 and after, the Opperhoofd played a mediating and infomative part in the negotiations between Japan and the foreign nations. ( Cf. inv.nrs. 1688-1717; Van Kleffens, p. 31-39 and van der Chijs, passim. )8. The Dutch trade with Japan.

The different trade-systems, wich were used on Hirado and Deshima in the course of two and a half centuries, have been described in detail by Nachod, Feenstra Kuiper, Meylan, Lauts, van der Chijs and others. Therefore only some main characteristics, especially those with a bearing on the archive, will be mentioned here. Until 1628 the Japan trade of the United Company has not been hampered by any limitations from the side of the Japanese authorities. After a four-year period, during which trade practically came to a standstill - caused by the doings of the Governor of Formosa, Pieter Nuyts - in 1628(-26) it was restricted more and more by Japanese prescriptions, such as export-embargoes, fixations of maximum amounts and prices, conditional sales, etc.

After 1725 the "Keizerlijke Geldkamer" (Imperial Money Chamber), acting as an exchange- and creditbank for the Company, was charged with the total purchase. This Chamber placed orders with the Company and in return gave a certain amount of trade goods, of which the most important were copper and camphor. It was a privileged commercial corporation that netted the overseas trade from the Imperial Treasury. ( Feenstra Kuiper, p. 111; Mansvelt, ) Handelsmij. ( p. 198. ) Beside the trade of the United Company, the so called "Kompshandel", existed the Kambang-trade or private trade, formally instituted in 1685. ( The origin of the word 'Kambang' is uncertain. According to Van der Chijs, p. 391, it was derived from the Chinese word 'kan-pan', i.e. show (of goods on) shelfs, or public auction. The expression 'Kompshandel' ('Comp(any)'s trade') remained in use also after the dissolution of the United Company in 1796. ) The "Heeren Zeventien" ('Gentlemen Seventeen' or the Board of Directors of the United Company) only grudgingly permitted their servants in Japan this elsewhere forbidden practice. It was desired, however, by the government of Nagasaki because the petty merchants of this town, not being able to engage in bulk trade, thus found an opportunity to take part in the retailing of the rather small invoices in the Kambang-trade. Like the 'Kompshandel' it was exactly regulated by Dutch and Japanese alike. Every dutchman on Deshima, including the captains of the ships, had a fixed share in the total turnover allowed. The restriction to a certain maximum led to extensive smuggling; the Japanese caught in the act often were executed, the Dutchmen banished from Japan. From autumn 1826 till autumn 1829 the Kambang-trade was carried on by the "Societeit van Particuliere Handel op Japan" ('Society for the Private Trade with Japan'), a creation of the Opperhoofd G.F. Meylan. ( Cf. inv.nrs. 1593-1601. ) The purpose was to cut the expenses by buying and selling on joint account. Only the officials on Deshima and the captains of the ships, trading to Japan, could participate. Unfortunately, Meylan's scheme did not come up to expectations, for various reasons. From 1835 till 1855 the Kambang-trade was let out to a Batavian merchant, while the officials at Deshima got a compensation for the loss of extra income. After 1855, the Government of the Dutch Indies took charge of it. The "Kompshandel"was liquidated formally in 1857, but was continued until 1860, as was the Kambang-trade. The "Aparte of nieuw geschikte handel" ('Seperate or newly established trade') dates from1804. The Opperhoofd Hendrik Doeff in that year agreed with the Money Chamber that the Dutch government should import some articles in special demand, such as lead, mercury and sapan-wood, in exchange for an extra amount of camphor. The credit money of the Dutch, the so-called "toegift" ('bonus') was booked on the Kambang-account. ( Inv.nr. 557, G.F. Meylan to the General Audit Office at Batavia, 20 November 1829. In later years, this credit amounted to a considerable sum, because there was a shortage of Japanese camphor for export. The result is a fading away of the original difference between (Dutch) Government trade and private trade. ) Under the name of "eis- en geschenkgoederen" ('goods in demand and gifts') the Dutch imported various luxury articles, books, instruments etc., which were demanded separately by the Shogun and other Japanese authorities. The demands of the Shogun were paid for on the Company-account, the others on the Kambang-account. ( The titles of the accounts are varying; cf. inv.nrs. 1449d, 1450d. ) These "geschenkgoederen" ("gifts") ought not to be mistaken for the real gifts to the Japanese, handed over on the occasion of the journey to the Shogunal Court. ( Cf. inv.nrs. 1161-1305, 1819-1831 and the annexes to inv.nrs. 1431b, seq, 1783-1797, 1803-1818. ) The Dutch took due notice of the nature and amount of the Chinese trade to Nagasaki, the Chinese being their only competitors. ( In 1685, two thirds of the total import amount were allotted to the Chinese. This distribution roughly corresponded with the existing situation. Cf. Nachod, p. 389 seq.). ) With the help of the Japanese, lists with data about the Chinese import and / or export were compiled every year. These lists have been incorporated for the most part in the daily records of the factory. ( Cf. the note to inv.nrs. 53-249. See also inv.nrs. 661, 823, 1449g, 1572. ) Prices were put in teal's ("thaylen"; "teilen"), initially a Sino-Japanese measure of weight (37,565 grammes), later a standard of value (37.565 grammes of silver). In the trade with the Dutch the so-called "Compagniestael" ('Company's teal') was used as money of account. The value of this teal in the course of years declined from 70 'stuivers' Dutch money (in the 17th century) to 32 'stuivers' (around 1800). For the Kambang-trade a special tael was put into use, which held a higher value. In 1818 the 'Kompstael' was fixed at 40 'stuivers' or 160 'duiten' Dutch Indies money, the Kambangtael at 192 'duiten'. The rate of exchange was accordingly: Dutch guilder: Dutch Indies guilder - 2 : 3, Kompstael: Dutch Indies guilder - 3: 4,8. ( Nacod, p. 134 seq.; Lauts, p. 283 ; inv.nrs. 50, 660. ) To close this paragraph, something must be said about the tradegoods, imported in or exported from Japan by the Dutch. In the 17th century, raw or spun silk (from China, Siam or Bengal), deerskins, ray hides (from Siam), lead, mercury and sapan-wood were the most importants imports, which were traded against silver, gold, copper, camphor and ( in lesser quantities) lacquerwork and porcelain. From the second half of the 17th century, cotton fabrics from India and several textiles from the Netherlands are of growing importance for the Japanese market. After 1668, when the export of silver was forbidden, the most important Japanese products were copper and camphor. Dutch and Indian textiles, sugar, sapan-wood, lead and tin were the principal imports down to the middle of the 19th century.

The periods 1633-1640 and 1652-1672 were extra-ordinary profitable for the Dutch. In 1636, the profit on import alone amounted to 1,5 million guilders, in 1638 it nearly reached 2,5 million guilders. The importance of the Japanese trade gradually declined, but the United Company did not abandon the factory ( although she threatened to do so several times during the 18th century) for fear that other nations would take her place. The monopoly position was very dear to the company and it was thought that in the course of time matters would change for the better. The importance of the factory after the dissolution of the United Company and the changed attitude towards Japan in the 1840's have been sketched already in par.7.

List of the chief factors, 1609-1860

The data of this list are mainly derived from the daily records of the factory. The persons named are those who actually served as Chief factor (Opper-hoofd), although in some cases they were not appointed as such. After 1641, the given year represents the greater part of the term in office; for instance, '1710' means: October/November 1709 - October/November 1710'. The full dates can be found in the daily records.

| Datum |

Gebeurtenis |

Period |

Chief factor |

| 1609 Sept. 20 - 1613 Febr. 13, |

Jacques Specx. |

| 1613 Febr. 13 - 1614 Sept. .. |

Hendrik Brouwer. |

| 1614 Sept. .. - 1621 Jan. .. |

Jacques Specx. |

| 1621 Jan. .. - 1623 Nov. 21 |

Leonard Camps. |

| 1623 Nov. 21 - 1932 Dec. .. |

Cornelis van Neyenroode. |

| 1932 Dec. .. - 1633 Sept. 5 |

Pieter van Santen. |

| 1633 Sept. 6 - 1939 Febr. 3 |

Nicolaas Couckebacker. |

| 1939 Febr. 4 - 1641 Febr. 10 |

François Caron. |

| 1641 Febr. 10 - 1641 Oct. 31 |

Maximiliaan Lemaire. |

| 1642, 1644 |

Jan van Elserack |

| 1643, 1645 |

Pieter Anthonisz Overtwater. |

| 1646 |

Reinier van Tzum. |

| 1647 |

Willem Verstegen. |

| 1648 |

Frederik Coyett. |

| 1649 |

Dirk Snoek. |

| 1650 |

Anthony van Brouckhorst. |

| 1651 |

Pieter Sterthemius. |

| 1652 |

Adriaan van der Burg. |

| 1653 |

Frederik Coyett. |

| 1654 |

Gabriel Happart. |

| 1655 |

Leonard Winnincx. |

| 1656, 1658, 1660 |

Joan Bouchelion. |

| 1657, 1659 |

Zacharias Wagenaar. |

| 1661, 1663 |

Hendrik Indijk. |

| 1662 |

Dirk van Lier. |

| 1664, 1666 |

Willem Volger. |

| 1665 |

Jacob Gruys. |

| 1667, 1669 |

Daniel Six |

| 1668 |

Constantijn Ranst de Jonge. |

| 1670 |

François de Haase. |

| 1671, 1673, 1675 |

Martinus Caesar. |

| 1672, 1674, 1676 |

Johannes Camphuys. |

| 1677, 1679 |

Dirk de Haas. |

| 1678, 1680 |

Albert Brevinck. |

| 1681 |

Isaac van Schinne. |

| 1682 |

Hendrik Cansius. |

| 1683, 1686 |

Andries Cleyer. |

| 1684, 1687 |

Constantijn Ranst de Jonge. |

| 1685, 1688, 1691, 1693; |

Hendrik van Buytenhem. |

| 1689, 1692, 1696 |

Cornelis van Outshoorn. |

| 1690 |

Bathasar Sweers. |

| 1694 |

Gerrit de Heere. |

| 1695, 1697, 1699, 1701 |

Hendrik Dijkman. |

| 1698, 1700 |

Pieter de Vos. |

| 1702 |

Abraham Douglas. |

| 1703, 1705, 1707 |

Ferdinand de Groot. |

| 1704 |

Gideon Tant. |

| 1706, 1708, 1710 |

Hermanus Mensing. |

| 1709 |

Jasper van Mansdale. |

| 1711, 1713, 1715 |

Nicolaas Joan van Hoorn. |

| 1712, 1714 |

Cornelis Lardijn. |

| 1716 |

Gideon Boudaen. |

| 1717, 1719 |

Joan Aouwer. |

| 1718, 1720 |

Christiaan van Vrijbergen. |

| 1721 |

Roelof Diodati. |

| 1722, 1723 |

Hendrik Durven. |

| 1724, 1725 |

Johannes Thedens. |

| 1726 |

Joan de Hartogh. |

| 1727, 1729, 1731, 1732 |

Pieter Bokesteyn. |

| 1728, 1730 |

Abraham Minnendonk. |

| 1733 |

Hendrik van der Bel. |

| 1734 |

Rogier de Laver. |

| 1735 |

David Drinkman. |

| 1736 |

Bernardus Coop à Groen. |

| 1737 |

Jan van der Cruysse. |

| 1738, 1739 |

Gerardus Bernardus Visscher. |

| 1740, 1742 |

Thomas van Rhee. |

| 1741, 1743, 1745 |

Jacob van der Waeyen. |

| 1744 |

David Brouwer. |

| 1746, 1748 |

Jan Louis de Win. |

| 1747, 1749 |

Jacob Balde. |

| 1750, 1752, 1754 |

Hendrik van Homoed. |

| 1751 |

Abraham van Suchtelen. |

| 1753, 1755, 1757 |

David Boelen. |

| 1756, 1758 |

Herbert Vermeulen. |

| 1759, 1760, 1762 |

Johannes Reynouts. |

| 1761 |

Marten Huysvoorn. |

| 1763, 1765 |

Frederik Willem Wineke. |

| 1764, 1766, 1768, 1769 |

Jan Crans. |

| 1767 |

Herman Christiaan Castens. |

| 1770 |

Olphert Elias. |

| 1771, 1773, 1775 |

Daniel Armenault. |

| 1772, 1774, 1776, 1778, 1779, 1781 |

Arend Willem Feith. |

| 1777 |

Hendrik Godfried Duurkoop. |

| 1780, 1782, 1783 |

Isaac Titsingh. |

| 1784, 1785, 1787, 1790 |

Hendrik Casper Romberg. |

| 1786, 1788 |

Johan Frederik Baron van Reede tot de Parkeler. |

| 1788 dec, 1 - 1789 juli 31 |

Hendrik Casper Romberg. |

| 1789 aug. 1 - nov. 23 |

Johan Frederik Baron van Reede tot de Parkeler. |

| 1791, 1792 |

Petrus Theodorus Chassé. |

| 1793 - 1798 |

Gijsbert Hemmy. |

| 1799 |

Leopold Willem Ras. |

| 1800 - 1803 |

Willem Wardenaar. |

| 1804 - 1817 |

Hendrik Doeff. |

| 1818 - 1823 |

Jan Cock Blomhoff. |

| 1824 - 1826 |

Johan Willem de Sturler. |

| 1827 - 1830 |

Germain Felix Meylan. |

| 1831 - 1834 |

Jan Willem Frederik van Citters. |

| 1835 - 1838 |

Johannes Erdewin Niemann. |

| 1839 - 1842 |

Edouard Grandisson. |

| 1843 - 1845 |

Pieter Albert Bik. |

| 1846 - 1850 |

Joseph Henry Levyssohn. |

| 1851 - 1852 |

Frederik Cornelis Rose. |

| 1852 - 1860 |

Jan Hendrik Donker Curtius. |

Geschiedenis van het archiefbeheer

1. The transfer of the first part of the archive (1609-1842) to Batavia (1852, 1860) and to the Netherlands (1862/3. The transfer of the second part (1843-1860) to the Netherlands (1909).

By regulation of 17 May 1852 of the Governor-General at Batavia, the Opperhoofd Mr. J.H. Donker Curtius was ordened to send the archive of the factory to Batavia, ".....and this, for the time being, including such a period, as seems to him, after consultation of his predecessor in office, the former Opperhoofd F.C. Rose, proper to be missed on Deshima." V.R.O.A. 1910 ( , p. 9. ) Rose thought that this was the case with the documents anterior to 1800. So this part was sent to the General Secretariat at Batavia, on which consignment Donker Curtius remarks in a covering letter, that the documents written in Japanese (the acts of safe-conduct and others) must be examined first by the Nagasaki officials. ( J.H. Donker Curtius to the G.-G., 4 Nov. 1852; inv.nr. 1652. ) These Japanese documents were sent to Batavia in September 1860 by the Consul-General of the Netherlands in Japan, together with the lacquered panel with the names of the Opperhoofden ( This panel is a Japanse piece of work, made around 1806. In 1850 it was transferred tot the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Cf. Levyssohn, p. 1-28, for a transcript of the contents, and Nachod, p. CXC-CXCIV, for a critical examination. ) and with the archive of 1800-1842. ( The Government Secretary at Batavia had asked for the transfer of the documents of 1800-1810 or 1800-1815. (Cons.-Gen. Yokohama, inv.nr. 1, nr. 133: Gov. Secr. to Cons.-Gen. in Japan, 1860 April 6; nr. 144: Cons.-Gen. to G.-G., 1860 Sept. 2, with annex: list of consigned documents.) The Consul-General did not mention the reason why the caesura was made at 1842, but this was done probably with a view tot the Shogun in 1844 and the Japanese refusal of the King's presents in 1843. Cf. par. 8, and Van der Chijs, p. 5-66. ) At Batavia the archive was preserved on the top floors of the Grain- and Iron-wharehouses, together with documents, produced by other outposts or by the "Hooge Regeering Batavia" ('High Government at Batavia'; henceforth indicated as: H.R.B.). Probably in this period the mixing of the Deshima documents with the last named archive has taken place. ( Cf. par.11. ) In 1862 and 1863 a part of these collections was sent to the General State Archives at The Hague, after a brief sorting. V.R.O.A. 1910 ( , p. 9; Ms.-inventory-H.R.B., Intr. p. 1-3. ) The Ambassador of the Netherlands at Tokyo finally sent the archive of 1843-1860 to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, (despatch, of 24 June 1909), whence it was received at the General State Archives in October 1909. V.R.O.A. 1910 ( , p. 9-10; the inventory (by dr. J. de Hullu) on p. 37-48; 397 items. )2. The original order of the archive. The descriptions by Mr. J.E. Heeres and Dr. J. de Hullu.

When the archive covering the period 1609-1799 was transferred to Batavia in 1852, the existing order almost remained unimpaired, which appears from the inscriptions and numbers on the covers of several volumes and from a summary list of the old archive, produced in 1852. ( Inv.nr. 1938. ) In this list the volumes, quires, bound documents and folders were described invariably as "bundels" (bundles), arranged in comprehensive series 'resolutions', 'daily records', 'incoming and outgoing letters', 'trade books and journals', etc. The documents written in Japanese characters were arranged seperately in chronological order. The same was done with the papers of the years 1800-1842, which remained at the factory for the time being. Mr. J.E. Heeres has left these arrangements unaltered for the most part in his description of the archive of 1888/1889. ( Ms.-inventory on cards by Mr. J.E. Heeres, at the General State Archives, The Hague. ) He split up the big series 'incoming and outgoing letters' in incoming and drafts("minuten") of outgoing letters, "letters of the High Government to various out-posts", etc. according to the principle of provenance, while he described the mixed-up documents from the archive of the High Government of Batavia as: "incoming drafts of letters" ("ingekomen minuutbrieven") or: "duplicates of letters received from Japan" The sequence of papers from 1800 till 1842 has been left intact by Heeres, just aswas the case with the group of documents written in Japanese, the account of the factory, etc. The second part of the archive, (1843-1860), received at the General State Archives in 1909, was described by Dr. J. de Hullu in 1910. He made a division into the archive of the Opperhoofd, the secret archive, etc., and removed the account books, - formerly arranged as annexes to the drafts of outgoing despatches - to separate series concerning trade. This classification has not been done very consistently, the accounts being

dispersed throughout the inventory.

3. The present order of the archive. Deviations from the principle of provenance. The state of preservation.

The present classification and description has been built on the work of Heeres and de Hullu, with due observance of the principle of provenance. The arrangement of resolutions, daily records and other closedseries as those of journals and ledgers was not altered fundamentally. The incoming and outgoing letters lent themselves to a more detailed classification in correspondence with several out-posts or with the Governor-General and his Council, while the letters from or to Japanese authorities were kept apart as far as possible.

A peculiar group is formed by the approved and confirmed drafts ("minuten") of incoming letters and the engrossed copies ("expedities") of outgoing letters from or to Governor-General and Council. These proceed from the archive of the High Government at Batavia, which is proved by inscriptions on the covers of the volumes. To place these items in the H.R.B. - archive, in accordance with the principle of provenance, did not seem desirable, on the one hand because there exists only a fragment of the said archive in the repository of the General State Archives (cf. par.9), on the other hand because these letters fill some gaps in the regular series of Deshima - documents. Inversely, a small number of volume, belonging to the Deshima - archive, got among the H.R.B. - archive. These are mentioned in part F of the inventory, together with the documents that by various causes got among other collections. The items, described in Ch. VIII, first period (Documents relating to trading stations in Asia) may also proceed from the H.R.B. - archive, but this cannot be established with certainty.

The items covering the period 1843-1860 were again dealt with separately in the present description. As was remarked in par. 7, the character of the factory was changed during the 1840's which change is shown in the archive by the existence of subdivisions containing secret documents, the papers of Donker Curtius acting as an official envoy, and cash-books, partly relating to the Vice-Consulate on Deshima after February 1860. Therefore it seemed proper to maintain the division of the archive in two periods, connected none the less by a consecutive numeration and a classification that corresponds as much as possible.

The archive, which covers a shelflength of 30 metres, has been preserved on the whole in a good state. A few of the older volumes resolutions, daily records, registers with letters) have suffered from moisture or insects. The documents of the second period have been damaged more, in proportion to their quantity. Those of 1843 are heavenly waterstained or riddled with wormholes, those of 1848 are nearly all missing.

The amount of loose documents is comparatively small; volumes, quires, and sets of bound documents form the greatest part. The bindings of the volumes in the series of correspondence with Governor-General and Council areare often broken, but none the less the volumes are discernible as such.

4. The classification of the trade books in connection with the book-keeping.

The outposts of the United Company had an account current with the "Comptoir-Genereal" (i.e. the Head Office) at Batavia. ( Mansfelt, ) Rechtsvorm ( , p. 91-92; Glamann, p. 25-252. ) The starting point of the book-keeping at the factory was the list of cash money and goods in store, called "Effecten" (Stocks), "Restanten" (Remnants) or "Capitael" (Capital), or - as was the case on Deshima - "Transport van 'sCompanies negotie" (Amount carried of the Company's trade). The account current with Deshima, kept at the Head Office in Batavia, was debited with the amount of this "Capital", just as for the worth of the cargoes to Deshima and for the profits made. On the credit-side were booked the outgoing cargoes, losses, and expenses of the factory. The counter-account at the factory (i.e. the account called "Comptoir-Generaal" on the first folio of the ledger) was credited or debited with these amounts, proceeding from the balances of the several ledger-accounts. At the end end of the trade-season, the account "Comptoir-Generael" was balanced with the "Capital", which sum appears at the head of the credit-side in the factory's ledger of the following season. In accordance with this procedure the various series of tradebooks are classified. First the general and yearly reports on trade and on thebook-keeping of Deshima are described: nrs. 659-716. Nrs. 717-1120 containthe account-books proper; documents concerning cash amounts, stocks and cargoes; journals and ledgers. The items numbered 1121-1354 are annexes to, orextracts from the journals and ledgers (accounts of profit-and-loss, expenseaccounts), whereas nrs. 1355-1422 concern next year's trade. (Lists of goods in demand and estimates of goods to be imported).

Several of these series end around 1795. This is probably due to careless personnel and disorderly book-keeping rather than to loss of the documents. Matters became still worse with the death of the Opperhoofd GijsbertHemmy during the journey to Edo in 1798. The wharehouse custodian Leopold Willem Ras, who served as a provisional Chief in the next two years, turned out to be unfit for his task. In 1800, the new Opperhoofd Willem Wardenaar straightened the affairs. ( Veenhoven, p. 25-26. ) Several new types of account and reports were introduced, otherswere disposed of, combined or continued with alterations. As has been said in par. 10, the archive covering theyears 1800-1842 was arranged chronologically in 1852, the documents of each yearbeing put together in one portfolio. After the removal of resolutions, daily records, reports on trade, incoming and outgoing letters, etc., a number of pieces concerning the book-keeping remained, which were not suited to aclassification in series. This is the case particularly with the papers from 1800 to 1830. It may be said to be partly a result of Wardenaar's doings.Therefore the chronological arrangement was maintained, a descriptive list beingmade of the contents of each unit: inv.nrs. 1423-1463.

The classification of the trade books from 1843 to 1860 has been done in accordance with the principles explained in the first part of this aragraph. The so-called "rekening-courant" ( the term appears in 1818) is not an account current with Batavia, but must be called a cash-balance ( kas-rekening).

5. Entries and expedients for the use of the archive.

In a number of cases, tables of contents ('tafels'), post-books ('agenda's') and indexes ('indices'; 'klappers') are extant in the volumes of resolutions, daily records, letters and reports, wich is mentioned in a note to the item concerned. Inv. nrs. 356-425 and 503-528 contain lists of incoming and outgoing letters and annexes, often not in accordance with the actual contents of the volumes. Inv. nr. 52 is a loose repertory ('repertorium') with an index ('klapper') on orders from Gentlemen Seventeen and Goverenor-General and Council. Such repertories, partly proceeding from the Deshima-archive, are to be found in the archive-H.R.B. (Cf. Part F). Inv.nr. 1572 contains a very concise and inaccurate summary of the documents presented at Deshima in 1826, with some notes about the volumes then missing. Inv.nr. 1938 gives a complete summary of the documents, transferred from Deshima in 1852, whereas inv. nr. 1688 is a detailed inventory of the secret archive.

The article by T. Itazawa ( Cf. the list of quoted sources and literature for the books and articles mentioned in this and the following paragraph. ) includes a name-list of the Opperhoofden, with the dates of the daily records produced during their term in office, covering the period 1631-1860. M. Kanai in his contribution on Donker Curtius not only deals with the transfer of the Deshima archive to the Netherlands but gives also a survey of Dutch archival sources relating to Japan, and of Dutch archival management and institutions. At the Historiographical Institute (Shiryo Hensan-jo) of the University of Tokyo a series of volumes about historical documents relating to Japan in foreign countries is in the course of production; five volumes wil be dedicated to the documents about Japan, Formosa and China, reposing is the General State Archives. Volume I, part I of these five has appeared already in 1963. This volume contains a detailed survey of the Deshima-archive as far as it was transferred to Batavia in 1852. (1614-1800, with the daily records extending to 1831). The items were mentioned in the order, adopted by Heeres in his ms.-inventory, (Cf. par. 10), with a descriptive list of each item added. The survey is partly in Dutch (caption titles being copied from the documents), partly in English. The portfolio-numbers of 'Heeres' inventory are mentioned also. Therefore, to facilitate the use of the present inventory together with the survey, a concordance of inventory-numbers and portfolio-numbers has been given hereafter. The former numeration of the documents from 1843-1860 (inventory by Dr. J. de Hullu) is placed between brackets.

6. Publication of documents from the archive.

In the works of Van Dam, Valentijn, Montanus, Kaempfer, Nachod, Feenstra Kuiper etc. a great number of documents relating to the Dutch in Japan have been printed, the provenance of which cannot be established with certainty, at least not in the case of the older works mentioned. The editors of the Corpus Diplomaticum Neerlando-Indicum have used copies of documents from the Deshima-archive, which copies repose in other archives and collections. (With one exception: inv.nr. 646). Veenhoven in his thesis edited parts of inv.nrs. 275, 430, 435. 437/8, 533, 548, 542/5 as annexes.

The publication of inv.nrs. 50, 276, 646, 660, 1470, and 1602/3 is mentioned in the notes of the items concerned.

A survey of Japanese activity in this field naturally can be only cursory. N. Murakami edited abstracts of the daily records of the periods 1641 June 25 - 1645 November 29 and 1650 October 25 - 1654 October 31 in a Japanese translation; the edition of the 'Japans Dagh Register' by "Nichi-ran Koshoshi Kenkyukai" is mentioned in the list of quoted sources and literature and in a note to the daily records in the present inventory. The monumental series of publications by the Historiographical Institute mentioned above, may contain some Deshima-documents in a Japanese translation. (E.g. the "Dai Nippon Shiryo": Chronological Source-books of Japanese History from the 9th Century to the 19th Century).

De verwerving van het archief

Het archief is bij Koninklijk Besluit of ministeriële beschikking overgebracht.

Aanwijzingen voor de gebruiker

Openbaarheidsbeperkingen

Volledig openbaar.

Beperkingen aan het gebruik

Reproductie van originele bescheiden uit dit archief is, behoudens de algemene regels die gelden voor het kopiëren van stukken, niet aan beperkingen onderhevig. Er zijn geen beperkingen krachtens het auteursrecht.

Materiële beperkingen

Het archief kent beperkingen voor het raadplegen van stukken als gevolg van kwetsbare of slechte materiële staat.

A small number of papers in these archives is in a bad physical condition, as a consequence of which they cannot be applied for. A survey of the inventory numbers in question has been omitted here, because the physical condition and the resultant application possibilities are not of a permanent character (preservation, microfilming etc.). If applicable, you will be noted when applying by way of the terminal.

Aanvraaginstructie

Openbare archiefstukken kunnen online worden aangevraagd en gereserveerd. U kunt dit ook via de terminals in de studiezaal van het Nationaal Archief doen. Om te kunnen reserveren dient u de volgende stappen te volgen:

- Creëer een account of log in.

- Selecteer in de archiefinventaris een archiefstuk.

- Klik op ‘Reserveer’ en kies een tijdstip van inzage.

Citeerinstructie

Bij het citeren in annotatie en verantwoording dient het archief tenminste éénmaal volledig en zonder afkortingen te worden vermeld. Daarna kan worden volstaan met verkorte aanhaling.

VOLLEDIG:

Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Nederlandse Factorij in Japan, nummer toegang 1.04.21, inventarisnummer ...

VERKORT:

NL-HaNA, Nederlandse Factorij Japan, 1.04.21, inv.nr. ...

Verwant materiaal

Inventarisnummers van dit archief zijn in kopievorm beschikbaar

Bijlagen