The American Revolution had a significant impact on the Dutch Republic. The end of the eighteenth century was marked by a spirited exchange of ideas on liberty, political rights and state-building between the two Republics. But it was not merely ideas which travelled freely. People from both sides of the Atlantic sailed across the ocean for professional, political, and personal reasons, and testified to the great revolutionary events that were unfolding at the time. This led to numerous exchanges between American and Dutch politicians. In this blog Lauren Lauret focuses on Gijsbert Karel van Hogendorp and Thomas Jefferson.

The Dutch Republic was the first country to acknowledge the independence of the United States in 1782. An official delegation set sail to Philadelphia the following year and Van Hogendorp joined them in a military capacity. His journey was a transatlantic and revolutionary version of the traditional Grand Tour: the Old World visiting the New. During the trip he wrote an extensive number of thematic and philosophical letters, now kept by the National Archives of the Netherlands in The Hague. He would later draw on this material when working on the new constitution of the Dutch Restoration government in the 1810s. In the process, Van Hogendorp retained the institutions of the Batavian Revolution, while providing them with their traditional, prerevolutionary names. A transatlantic perspective helps us to better understand the pivotal contributions of both Jefferson and Van Hogendorp to the American and Dutch constitutions respectively.

The best-informed man of his age I have ever seen

After meeting Van Hogendorp in Annapolis, where Congress had assembled, Jefferson recommended him to George Washington “as the best-informed man of his age I have ever seen.” Of course, Jefferson could not foresee that Van Hogendorp would later become the main author of the Dutch constitution, but, as he wrote to the young man, he was much impressed with his abilities:

Your thirst after knowledge, your capacity to acquire it, your dispositions to apply it to the good of mankind [..] give your country much to hope from the continuance of your life.

Such praise no doubt boosted the intellectual ambitions of the twenty-year old youth who relished the exchange of ideas on government with Jefferson from the moment they met. At first glance, Jefferson and Van Hogendorp would appear to be unlikely friends. They occupied opposite ends of the spectrum as far as fundamental questions were concerned. Jefferson championed popular sovereignty and individual state power. In contrast, Van Hogendorp believed that the people should be firmly kept in check and that the limitations on the powers of Congress were detrimental to the American Republic. Nevertheless, the exchange of letters set Van Hogendorp’s mind on fire and he bombarded Jefferson with questions. On reading a draft of Jefferson’s Notes of the State of Virginia in 1784, he asked a poignant question:

Give me leave to put You in mind of the articles of Your description of Virginia, which You granted me to have copied. I should wish to know whether Your Negroes marry, or what proportion do. One Evening in the Yerseys, riding on very slow on my fatigued horse, I conceived an idea that gave me great Satisfaction. It leads to develope the history and destination of man. In consequence of it I have drawn a rough sketch of a system of Nature, of Society, of Government and of Politics. I am not able now to Send You a copy, but intend doing it afterwards.

Study the laws to simplify them

A central idea running through Van Hogendorp’s notes is the “simplicity” of the American people. This would also become a key term in plans to reform the government of the Dutch Republic. Van Hogendorp carefully observed how the Massachusetts legislature went about simplifying the state’s legislation in December 1783:

Committees do most of the work really, or the main combatants walk up to each other during a debate and settle the matter. They do not always turn a committee report into a state law, nevertheless the report is influential. Several matters are trusted in the hands of committees elected outside of the assembly: this way the most-esteemed are elected to study the laws to simplify them. Seventy [bills] were listed, three of those were presented to the assembly, and all of them spoiled by lucid comments.

According to Van Hogendorp, public finance was in need of simplification in both the ‘old’ Dutch Republic and the young American Republic. Most Dutch provinces had been unwilling to adapt their standard contribution to federal expenses when circumstances changed. In the light of this crucial political problem, Van Hogendorp was very interested in the design of American financial system. Jefferson commented on Van Hogendorp’s “short account of the finances of the United States” and Robert Morris—the initiator of the Bank of North-America—commented on his note on the “Bank of North-America.” The American states, like the Dutch provinces, wanted to maintain the quote system, which they regarded as an essential element of states’ rights. Van Hogendorp was of the opinion that in doing so the young American Republic ran the risk of making the same mistakes as his homeland and informed Jefferson accordingly.

In his notes, Van Hogendorp also reflected on the benefits of Dutch-American financial and commercial collaboration, which was of course the main purpose of the delegation of which he was part. “The lack of money is a general complaint in America,” he observed. Both the American people and several of the states desired to establish a central bank, but lacked sufficient funds to do so. Regardless of the source of funding, Van Hogendorp opined that “the power invested in that bank should be placed in the state.” He believed Dutch capital should be used, as “we would benefit from foreigners, while we pay them a service.” American imports of raw materials to the Dutch Republic would reduce commodity costs and thus support Dutch industries, while the surplus of funds accumulated by wealthy merchants would flow out of the country in a secure and profitable way. In a way, this is what happened subsequently: Amsterdam trading houses and banks supplied a considerable number of loans to the United in the 1780s and 1790s. Van Hogendorp’s observations contain the kernel of an idea that would be put into practice in the Netherlands after 1813: a central bank with close ties to the national government.

After Van Hogendorp returned to the Netherlands and Jefferson was stationed in Paris in 1785 their correspondence continued for another year or so. Jefferson sent Van Hogendorp a copy of his Notes on the State of Virginia as well of the proposed revisions of the laws of Virgina. The proposals, based on Jefferson’s natural philosophy, emphasized gradual political reform and the composition of republican constitutions. Van Hogendorp expressed his hope “to communicate some reflexions” soon, but for the time being, he found the “article of natural history” very pleasing. Van Hogendorp full-heartedly agreed with Jefferson that “every natural production, in similar circumstances, generally speaking, [was] the same with you as with us”. In September, he told Jefferson which other documents he would also like to study:

The Code of laws Your friend will send me As I am now studying more particularly the civil law; that of a people understanding its rights, that which is built on common sense, rather than on authorities of former times, that which takes its origin from an enligthened nation (which You Surely allow the English to be), must be perculiarly interesting and worthy of my whole attention.

This letter points to the origin of Van Hogendorp’s central notion as author of the Dutch constitution in the early nineteenth century: maintaining the governmental institutions of the Batavian Republic under an early-modern name. He had adopted the idea that history was not the sole source of political legitimacy. In this case, Van Hogendorp took his lead from civil law which employed common sense as a source of legitimacy. From the Notes Van Hogendorp must have understood that Jefferson too believed that traditional forms of authority had to yield to human reason and common sense, which had become prevalent in the later eighteenth century.

The bond which connects rulers to the ruled

Van Hogendorp adopted another crucial idea from the United States: popular influence as a requirement for a stable government. In reacting to the Dutch translation of Richard Price’s Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty, Van Hogendorp posited that political equality of men was an illusion, as equal distribution of possessions was its necessary prerequisite. In America he had witnessed wise men fall victim to the “tendency of the people” to believe in the future equal distribution of wealth and possessions. Van Hogendorp feared that the potential growth of the United States would satisfy only the most ambitious: “Interest and custom form the bond which connects rulers to the ruled.” This also applied in the United States, as the Americans regarded the wealthy free states of Mexico and Peru with suspicion. Rulers should therefore take into account that there would always be conflicts of interest among the people they ruled. And increased wealth among the population could challenge, or even topple, those already in power. Therefore, a government would act wisely if it allowed the people a say over governmental matters. The main issue was how to manage the people’s influence as installing a system of checks and balances was essential to state building. Van Hogendorp openly doubted whether wealth or nature should be determinative factors. In any case, America had provided Van Hogendorp with an ingenious way to solve this:

In the new governments of the American free states, every independent inhabitant has the right to elect members of the commons. But not everyone has the right to elect members of the Council or the two bodies of the legislature. One has to possess a certain property, or double the amount of money, to be elected to the commons; and more so to sit in the Council; and most to be Governor.

The executive an illustrious family

The correspondence between Van Hogendorp and Jefferson was not just one-way traffic. Van Hogendorp supplied Jefferson with information about the Dutch Republic, including his opinion on the risk of concentrating power in the hands of a single executive officer for an entended length of time. To Van Hogendorp the Dutch Republic was similar to England, where “unequality of fortunes has confined the greatest share of power to a few hands”. He explained how the House of Orange became to regard the highest public office, the stadtholderate, as its private possession: “It is become necessary with us to place at the head of the executive an illustrious family which excludes forever any other one, and prevents a kind of civil war at every vacancy.” He pointed to Dutch history to highlight the dangers:

The first Stadholders held from the king the same power and in the same way as Your Governors do from the people at large. [..] The [Dutch Revolt] made them Stadholders of the State, instead of the King’s and lately they have been declared hereditary. The nation at that epocha has heaped on her new Stadholder’s head every honour and advantage almost that she was able to bestow. She now has been repenting of her former profusion. But alas! instead of resting satisfyed with her success in reassuming such rights as must be her’s alone in order to entertain an equipoise to the Stadholder’s influence, the nation is imposed upon by some daring men who should wish to lay the foundation of their own greatness on the ruin of the Stadholder’s constitutional authority.

Thus Van Hogendorp explained how upon his return from the United States, he found his homeland on the brink of civil war. Everyone had to take sides in the struggle between the so-called Patriots party and the Orangist party. Meanwhile Jefferson had arrived in Europe in 1784 and was informed by Van Hogendorp—a fierce critic of the Patriot movement—about the turmoil. This partisanship made Jefferson skeptical about the future of the Dutch Republic:

I feel a sincere interest in the fate of your country, and am disposed to wish well to either party only as I can see in their measures a tendency to bring on an amelioration of the condition of the people, an increase in the mass of happiness.

As the Dutch Republic descended into political turmoil in 1787, the delegates of the American states to the Constitutional Convention taking place in Philadelphia used the Dutch as an example to demonstrate what the future United States should not become. However, the Dutch Republic had been referred to in a more positive way during the constitutional debates in the individual states. From a Dutch perspective, it is striking to note that many American state constitutions included a mechanism to ensure only Protestants had access to public office well into the nineteenth century.

American Vestiges in the Dutch Constitutional Committee (1815)

After the monarchy in the Netherlands was reestablished in 1813, Van Hogendorp became chair of the committee entrusted with drafting the new constitution. Now he could use American examples to finetune his thoughts on government into a founding document. He had closely studied the Massachusetts Constitution, in which the executive was the strongest of all of the states. Likewise, the American federal constitution of 1787 had granted extensive powers to the president. Taking his lead from these examples, Van Hogendorp’s draft constitution allocated great power to the executive. In practice, this power would be given to the son of the last stadtholder: King William I (1776-1843).

Van Hogendorp also devoted considerable attention to the idea of a parliament divided into a lower house and a senate. This was “a cardinal point” according to him, but its implementation was hotly contested. Whereas Americans had feared that representatives “like those in Holland” could stay in office for life, Van Hogendorp faced opposition from members who argued that a monarchy needed nobility to keep the lower house in check. Van Hogendorp was not opposed the idea of two houses per se, but he could not agree to hereditary membership in the senate. After the decision on the two houses of parliament had been made, the committee had to decide whether debates in the lower house should be held in public. The majority of the committee, including Van Hogendorp, was in favour of public debates. Supporters referred to the United States to point out the benefits of public debates. Debating in public and publishing the proceedings were the only ways to maintain national trust in parliament and nourish the public spirit, the argument ran.

Despite Van Hogendorp’s American experience, he did not recognize a fatal mistake in the new constitution of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. He had failed to secure equal representation of the various parts of the kingdom in the lower house. The population of the southern provinces—now Belgium—outnumbered the northern by two to three. The Protestant north feared being outvoted by Catholics from the south. Van Hogendorp’s stance shows the American influence on his conception of political representation. In the American Republic, the issue of representation in Congress was not addressed definitely. Another member of the committee recalled that the early American Republic had changed its system of representation within a few years after its independence: while the thirteen American states each had had one vote in Congress, they were now “waiting for a general cadastre of the lands” to redistribute the votes accordingly. Van Hogendorp believed that soil, wealth, and education should determine the number of delegates rather than population size. He also insisted that the Dutch colonial territories should be taken into account, in an echo of the American revolutionary argument regarding taxation and representation. This would mean the Dutch population, including colonies, would outnumber the Belgian south, which did not have any colonies, by two to one. Taking its lead from the American Republic, the Dutch constitutional committee proposed an unequal representation of the northern and southern parts of the new state. But in true Van Hogendorp fashion, it presented this as a continuation of the Union of Utrecht of 1579: the north and the south should be regarded as equal partners in the Kingdom, as the provinces of the Dutch Republic had been until 1795. Therefore the north and south should have an equal share of the vote in the new assembly. It did not last. Within fifteen years, the southern representatives separated from the north during the Belgian Revolution of 1830.

Conclusion

What do these exchanges between the Dutch and American Founding Fathers tell us about the principles of redesigning governmental structures in the Revolutionary Era? Without Van Hogendorp’s study of the American Republic, the Dutch state may have looked very different in the nineteenth century. Of course, the exchange of ideas did not stop at the turn of the century. Jefferson commemorated his stay in the Netherlands in his 1821 autobiography. He remembered Van Hogendorp as a “royalist” who criticized the central role of the stadtholder. Shortly before Jefferson visited the Dutch Republic in 1788, Prussian troops had restored the House of Orange to the stadtholderate. Jefferson regarded the stadtholder as the main problem in the constitution of the Dutch Republic, as the English crown forced the stadtholder into the unenviable role of a “servile Viceroy of a foreign sovereign”.

By 1821 however, Van Hogendorp had shed his reputation as a royalist. Instead public finance became the central theme of his political work. He upheld the principles of public finance that he had studied in the U.S. in the 1780s. However, the Dutch king wanted to limit parliamentary control on the state budget as much as possible. When Van Hogendorp voted against the budget in 1819, William I regarded this as an act of treason and stripped Van Hogendorp of his honorific title as Minister of State. The Belgian Revolution put the issue of constitutional revision on the political agenda: Van Hogendorp published a pamphlet on the state’s credit and advocated the important issue of national finance that he had discussed with Jefferson decades earlier.

About the author

Lauren Lauret (Ph.D. Leiden University, 2020) is NWO Rubicon post doc researcher at University College London. Her most recent monograph is Regentenwerk. Vergaderen in de Staten-Generaal en de Tweede Kamer, 1750-1850 (Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2020). Her forthcoming research publication, in collaboration with Karwan Fatah-Black and Joris van den Tol, is Serving the Chain? De Nederlandsche Bank and the Last Decades of Slavery, 1814-1863 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2023).

About the blogseries

This is the nineteenth installment in a monthly series of blogs telling stories about the rich history shared by the American and the Dutch peoples. Authors from both countries present accounts of their own choosing, from a wide variety of perspectives, in order to give as full a picture as possible of the triumphs and heartbreaks, delights and disappointments that happened place over hundreds of years of shared history. Not all these stories are “feel-good history’, however. While the relations between the Dutch and the Americans have for the most part been stable and peaceful, their shared history contains darker moments as well. Acknowledging that errors have been made in the past does not diminish this friendship but, rather, deepens it.

Further Reading

Burg, Martijn van der, “Transforming the Dutch Republic into the Kingdom of Holland: The Netherlands between Republicanism and Monarchy (1795-1815),” European Review of History 17.2 (2010): 151–170.

Cleave, Peter Van, “Revolt, Religion, and Dissent in the Dutch-American Atlantic: Francis Adrian van Der Kemp’s Pursuit of Civil and Religious Liberty” (ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2014).

Kaplan, Lawrence S., “The Founding Fathers and the Two Confederations: The United States of America and the United Provinces of the Netherlands, 1783- 1789.” A Bilateral Bicentennial: A History of Dutch-American Relations, 1782- 1982. Ed. J.W. Schulte Nordholt and P. Swieringa (Amsterdam: Bow Historical Books, 1982). 33-49.

Lauret, L. B., & D. G. A. Alkemade, “Four Founding Fathers on the Road: New Government Design in the United States and the Netherlands, 1776-1815.” Revue Française D’ Etudes Americaines, 173(4) (2022), 78-96.

Meerkerk, Edwin van, De gebroeders Van Hogendorp. Botsende idealen in de kraamkamer van het Koninkrijk (Amsterdam: Atlas Contact, 2013).

Mijnhardt, Wijnand, “The Declaration of Independence and the Dutch Legacy.” Opening Statements: Law, Jurisprudence, and the Legacy of Dutch New York. Ed. A. M. Rosenblatt & J. C. Rosenblatt (Albany: SUNY Press, 2013), 55- 66.

- Nicolaisen, Peter, “John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and the Dutch Patriots.” Old World, New World: America and Europe in the Age of Jefferson. Ed. A.J. O’Shaughnessy (Charlotte: University of Virginia Press, 2010), 105–130.

Sources

National Archives of the Netherlands, collection 2.21006.49 (Van Hogendorp Family Papers). This collection contains several documents pertaining to his travels in America, including diaries (inv. nr. 50, 54), letters to his mother (inv. nr. 12-13, 36), notes on various topics (inv. nr. 54), printed materials that Van Hogendorp collected (inv. nr. 55), as well as letters and other documents in Jefferson’s hand (inv. nr. 102).

National Archives, Founders Online https://founders.archives.gov/

Illustrations

Gijsbert Karel van Hogendorp, by Jean François Valois (1835) after Cornelis Cels, 1819. Collection Haags Historisch Museum, Den Haag, 1924-0009-SCH, https://ais.axiellcollections.cloud/HAAGSHM/Details/collect/1759.

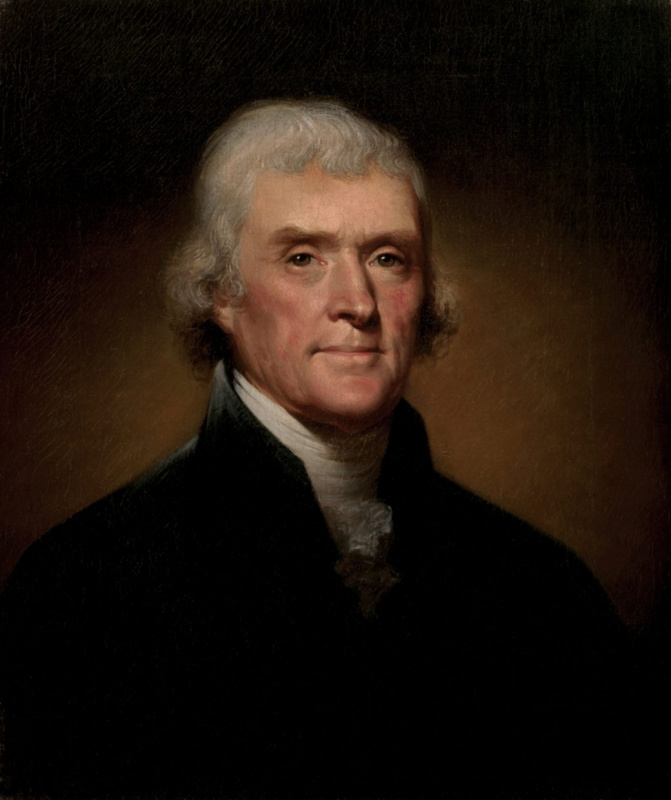

Thomas Jefferson, by Rembrandt Peale, 1800. White House Historical Association, 1962.395.1..

A Map of the Harbour of New-York by Survey,” ca. 1784. Manuscript map National Archives of the Netherlands, collection 2.21.006.49, inv. nr. 54.

“Proposals for a Bank,” ca. 1784. National Archives of the Netherlands, collection 2.21.006.49, inv. nr. 55.

The restoration of the Dutch monarchy on 21 November 1813 at the house of Gijsbert Karel van Hogendorp in The Hague. Historicized painting by Jan Willem Pieneman, 1828. Rijksmuseum SK-A-1558, http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.7423.

Draft of the 1815 Constitution of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. National Archives of the Netherlands, collection 2.02.01, inv. nr. 134, https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/onderzoeken/archief/2.02.01/invnr/134/file/NL-HaNA_2.02.01_134_01