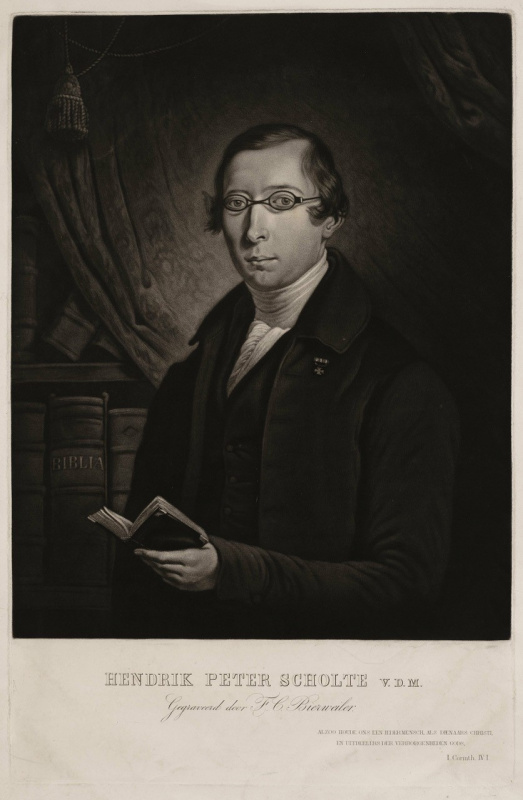

What does it mean to be of Dutch extraction in the United States? Pella, situated on the Iowa plains, was the destination of choice for hundreds of Dutch families, led by Hendrick Pieter Scholte, after the Afscheiding (Secession) of 1834 split the Dutch Reformed Church. What is still Dutch and what has changed over time? Valerie Van Kooten, Executive Director of the Pella Historical Society and Museums, tells us about her childhood.

My name is Valerie Terpstra Van Kooten. I was born in Pella, Iowa, and raised on a farm two miles west of Pella. I knew from the earliest days that the abstract to our farm documented that the land was originally transferred from Hendrik Peter Scholte to Jacob De Haan and Cornelis Welle, dividing it into two farms, with my family purchasing the De Haan half in 1971. Later, I was to find out that almost everyone’s abstract in Pella showed Scholte as the original land holder. We weren’t unique in that.

Dutch Through and Through

As far back as I can determine, my ancestors on all four sides of my family were Dutch. On my mother’s maternal side were the Hoksbergens and Van Wyks, one of whom, Willem Pieters van Wijk, signed the 1834 Secession document. When the new Haarlemmermeerpolder provided more farm land in the 1850s, the Van Wyks first moved from Brabant to North Holland, and then emigrated to America in the 1880s. On my mother’s paternal side were the Beyers and the Van Zees, one of whom, Stephanus Van Zee, came with Scholte in 1847 on the Pieter Floris. The Beyers had long made their home in Veenendaal in Gelderland, where many still live.

My father’s side of the family came later. On his mother’s side, the Wouterses and the Van Oenens from Amersfoort came in 1909. I still remember my great-grandma Sientje Van Oenen, a petite woman who caught rainwater outside her window to wash her face. She had come to Iowa when she was twenty, alone. My father’s paternal side had a more interesting history. The Terpstras left Sint-Anna Parochie, Friesland, in 1892, ending up in Paterson, New Jersey, where they stayed for several years before moving to Iowa. The Vande Voorts left Dodewaard, Gelderland, in 1911, the parents and seven children, one of whom was my great-grandmother Marie Vande Voort Terpstra. She used to tell me a story about her own great-grandmother, Agatha Miering, who had been the daughter of a duke and who had been disinherited by her family for marrying one of the estate’s gamekeepers, a young mijnheer Vande Voort. I wondered for years whether this romantic love story were true and discovered, years later, that, by and large, it was. My husband’s family has a similar path---Arkemas, Van Kootens, Schuts, Bruxvoorts….all Dutch. You can imagine how surprised I was to send in my DNA sample to ancestry.com and found I was 21% Scandinavian. I guess it’s that Frisian Viking blood!

The fact is, many people in Pella can trace their Dutch roots back generations. And it shocked me, when I started college, that my classmates couldn’t go back more than two to three generations. They’d say, “Well, I’m a mutt,” or “I’m about ten nationalities all put together.” That was unfathomable to me. All of my childhood friends were Dutch, with last names of Rozenboom, De Zwarte, Huisman, and Langstraat. Any one of them could recite a genealogy without thinking twice. We were Dutch through and through and proud of it.

And, of course, we had Tulip Time. For three days in the beginning of May, we donned very inauthentic Dutch costumes and marched with our classmates in the parades. The costumes were incredibly generic, not from any province really, and more resembling Little House on the Prairie costumes. If it were unusually cold, our mothers would pin a lacy baby blanket around our shoulders and close it with a brooch. If being in Tulip Time wasn’t Dutch, what was?

Reformed and Christian Reformed

The one thing that did divide the Dutch into two camps in Pella was their church affiliation—there were those who belonged to the Reformed Church and mostly attended public schools. I didn’t know most of those kids, unless they happened to play softball on my city league team or attended my 4-H club. The Christian Reformed kids went to the Christian schools and ran in their own circles. Until I was in high school, I sincerely thought a “mixed marriage” was one where a Christian Reformed girl married a Reformed boy, or vice versa. Parents were very clear about this—if you marry outside your own denomination you’ll fight about where your kids go to school later. And to be honest, that was true. I saw several of my friends’ marriages battle it out on school choice. Maybe my mother was right on this. There were a few kids who mixed the two systems—maybe attended the Christian Reformed Church but went to public school or went to Christian School and the Reformed Church. My father was one of these and said he never felt as if he belonged in either camp. He swore he would never do that to his children.

Students at Pella Christian were often called “Offies,” a derogatory term that we weren’t sure what the origin of was. Years later I discovered it came from Afscheiding. So “offies” were separated, different. The ironic part of this was that anyone who came to Pella was part of the Afscheiding, not just the Christian Reformed folks. The term applied to us all. As the member of a particularly conservative Christian Reformed congregation in Pella, I was thoroughly catechized. Every Sunday morning after the service—and when I got older, on Wednesday nights—my peers and I lined up in rows of chairs in a small Sunday School room to be taught by elders in our congregation, men who were, six days a week, farmers and shopkeepers and teachers. They didn’t want to be in front of a group of fifteen 4th graders, I’m sure. And their teaching was largely uninspired, more of a regurgitation of answers back to the Heidelberg Catechism questions. You wanted to sit in the middle of the row, as the teacher started at the edge and asked the question, and the student answered, or tried to. Then he repeated the question to the second student. By the time he got to you, you had heard it answered several times. Rarely was this pattern changed. Even though the way we were taught the catechism was by rote—mechanical and stiff—I still treasure some of the questions and answers fifty years later. And I still believe those men did their best.

When I reflect on my growing-up years, I’m not sure what’s particularly Dutch, what’s particularly living on an Iowa farm, and what’s particularly American. Being on a farm meant we ate breakfast, dinner, and supper, not breakfast, lunch and dinner. Being Dutch meant we ate things like rice and raisins and “melk” pop and “oliebollen”, Being an American meant we celebrated July 4 and pledged allegiance to the flag. But often our lives were a unique hybrid that incorporated all of these things.

For example, the Yankee-Dutch words that we sprinkled through our language. Things were “vies,” (dirty), or “pooslijk,” (shabby) or a “ratzooi,” (rotzooi; a mess). Kids were “kanuists” (klungels; bunglers) or “zameled,” (stamelaars; whiners) or were a little “toot cowse” (kletskous; chatterbox). Again, college at a state university was the great awakening for me. The first time I told my roommate to get her “throop,” (troep; stuff) out of the bathroom and she looked at me with a bland stare there was the dawning realization that maybe that word wasn’t one that everyone grew up with.

Sundays

What was especially Dutch were the Sunday observances. You went to church twice on Sunday, at 9:30 and 7 p.m., and any other times than these were suspect. After the morning service you went to catechism and then home for Sunday dinner, which was always a pot roast with vegetables and homemade applesauce and a piece of pie for dessert. Sunday afternoons were for napping and little else. How we kids dreaded Sunday afternoons! We were forced to be quiet and stay in our rooms. As we grew older, we weren’t confined to our rooms, but we did need to stay silent while our parents slept. We knew there were non-Dutch kids in Pella who went out for ice cream or went to the beach on Sunday afternoons, but we knew not even to ask to do something like that. Wasn’t gonna happen. For us, it was no TV, no doing handcrafts, like knitting or embroidery, no riding bike. After church on Sunday nights, families visited at each others’ house; either we went somewhere or someone came to our house. I don’t remember a Sunday night without visiting someone or being the host.

Along with a legalistic observation of the Sabbath came another big no-no: dancing. While we kids danced in private at slumber parties and in each other’s basements, organized dances were verboten. The joke we often heard was, “Why don’t Dutch people have sex? Because it might lead to dancing.” The other two vices that the Christian Reformed Synod had labeled sinful in the 1920s were playing cards and movie-going, though by the time I was growing up, those were no longer observed. Just the taboo on dancing.

Some things have changed over the years and some haven’t. So you may ask, what are the Dutch in Pella like today? We still sprinkle our English with Dutch phrases. Even my grandsons will use the word “broekje” when talking about underwear. I still sing a Dutch nursery rhyme to my granddaughter, even though it’s now in English. My mother still calls me to tell about someone who is a “tobbit,” (tobber; worrywart) or a “dwaaskop,” fool. The Pella Dutch still have coffee time at 9:30 and 3:30; even the local companies set their break times at these hours. If you show up at someone’s house, you’ll be offered coffee time, even if that doesn’t include coffee.

And Sundays have changed, too. While most Dutch are still either Reformed or Christian Reformed, a sizeable number attend non-denominational churches in Pella. A few have wandered off to the Methodist or Baptist churches, and a handful are Catholic. While the Christian Reformed churches still have two services, the Reformed churches have only one. And most members of both churches have no problem going out to eat for lunch on Sunday or running to Des Moines Sunday afternoon to do a little shopping. By and large, though, Pella is pretty quiet on Sundays. Tourists coming in for a day of sightseeing amble, confused, through the quiet streets.

And there’s still the Dutch Calvinistic tendency of a congregation to split from a body thought to be too liberal. In 1998, my CRC congregation split, with more than half leaving to form a more conservative Reformed congregation. I had heard from older members in my church who remembered the split in the 1920s that led some to leave the CRC and start the Protestant Reformed Church. One woman told me that she still cried about the pain that had caused among families. When our congregation split, I knew what she meant. It was a painful thing to be left behind and labeled “less pure” by those leaving. Now it’s the Reformed Church in America splitting. Is it something in our genes?

Tulip Time

Tulip Time has become bigger over the years, as we now welcome 250,000 visitors to our town of 10,000 during three days each year. And while the festival continues to grow, I am proud that it is largely uncommercialized. The original board of Tulip Time stated that the goal of the festival was to celebrate Pella’s Dutch heritage and settling in 1847. We do a good job of that, not allowing outside sponsors to come in and plaster their names all over, not allowing food stands in that aren’t owned by Pella people, and not having a carnival. Some might say this is too insular, but it helps us keep control of the brand and image and intent of the festival.

Cleanliness and pride of property still rule supreme. Everyone says, “Pella is a clean town,” by which they mean, I suppose, that you don’t see a lot of trash on the streets, and most homeowners keep their yards and homes looking nice. Spring and fall housecleaning still occurs, mostly by the older women in town. My thoroughly Dutch grandmother asked her non-Dutch daughter-in-law one year if she had begun her fall housecleaning yet. Her daughter-in-law, my aunt, was quite offended—was she implying that her house was dirty? My grandma was simply making conversation. Though the cleaning mania continues in many Pella homes, the contest to get your clothes on the line the earliest on Monday mornings is mostly gone.

The competition between the public and private school systems is not as intense, I don’t believe. Both are excellent schools; each has its good and bad qualities. Kids get to know their counterparts from the other school much earlier than we ever did, and that’s a good thing. Pella Christian’s marching band wear red wooden shoes; Pella Community’s athletes and students are known as “The Dutch.” You see more intermixing of Christian school kids in Reformed churches or the other way around. The stigmas are disappearing.

And Pella has exploded with non-Dutch, as our largest industries—Pella Corporation, Vermeer Corporation, Lely, PPI, Central College, the Pella Community Hospital—expand. We have a large number of Laotian, Vietnamese, and Indian citizens. We’ve dropped the bumper sticker, “If you ain’t Dutch, you ain’t much.” We are slowly become a more inclusive, welcoming city, but we have a ways to go. Maybe we do live inside a bubble in Pella, as we’re sometimes accused of doing. Maybe we do value things that have fallen by the wayside in many other towns. But my view, from inside the bubble, is pretty good.

About the author

Valerie Terpstra Van Kooten is Executive Director of the Pella Historical Society and Museums, which comprises a 22-building historical village and the Scholte House Museum. This blog is based on a contribution presented at the symposium “Enkele reis Pella,” organized by the Archief- en Documentatiecentrum van de Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland and held in Noordeloos in the Netherlands on 30 September 2022.

About the blogseries

This is the eleventh installment in a monthly series of blogs telling stories about the rich history shared by the American and the Dutch peoples. Authors from both countries will be presenting accounts of their own choosing, from a wide variety of perspectives, in order to give as full a picture as possible of the triumphs and heartbreaks, delights and disappointments that took place over hundreds of years of shared history. Not all these stories will be ‘feel-good history’, however. While the relations between the Dutch and the Americans have for the most part been stable and peaceful, their shared history contains some darker moments as well. Acknowledging that errors have been made in the past does not take away from this friendship but, rather, deepens it.

Further reading

- Buerkens, Clarence “Buck”, Buck Saw: Selected Articles of Pella History As They Once Appeared in the Pella Chronicle (Pella: Pella Historical Society, 2000).

- Douma, Michael J., How Dutch Americans stayed Dutch: An Historical Perspective on Ethnic Identities (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2014).

- History of Pella, Iowa, 1847-1987, 2 vols. (Dallas: Curtis Media Corp., 1988).

- Souvenir History of Pella: 1847-1922 (Pella: The Booster Press, 1922, re-published Pella Historical Society, 2014).

- Van Stigt, History of Pella, Iowa, and Vicinity, translated by Elisabeth Kempkes, (Weekblad Print Shop, 1897, re-published Pella Historical Society, 2017).

- Webber, Philip E., Pella Dutch: The Portrait of a Language and Its Use in One of Iowa's Ethnic Communities (Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1988).

Sources

- Pella Historical Society and Museums, https://www.pellahistorical.org

- National Archives of the Netherlands, collection 2.07.01.03, Archive of the Department of Reformed and Other Worship, except Roman Catholic, 1815-1870, https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/onderzoeken/archief/2.07.01.03

- Archives of the Christian Reformed Church in North America, Hekman Library, Calvin University, https://library.calvin.edu/guide/collections/hh/crc_archives

- Archives of the Reformed Church in America, Gardner A. Sage Library, New Brunswick Theological Seminary, https://www.rca.org/about/history/archives/

Illustrations

- Portrait of Hendrik Peter Scholte. One of the leaders of the Secession of 1834, Scholte became the leader of about eight hundred Dutch immigrants to Iowa in 1847 and 1848. Stadsarchief Amsterdam, engraving by F. C. Bierweiler, ca. 1833-1840, https://archief.amsterdam/beeldbank/detail/0dc827fd-6f8b-7e23-d6ad-7bce2fa59a43

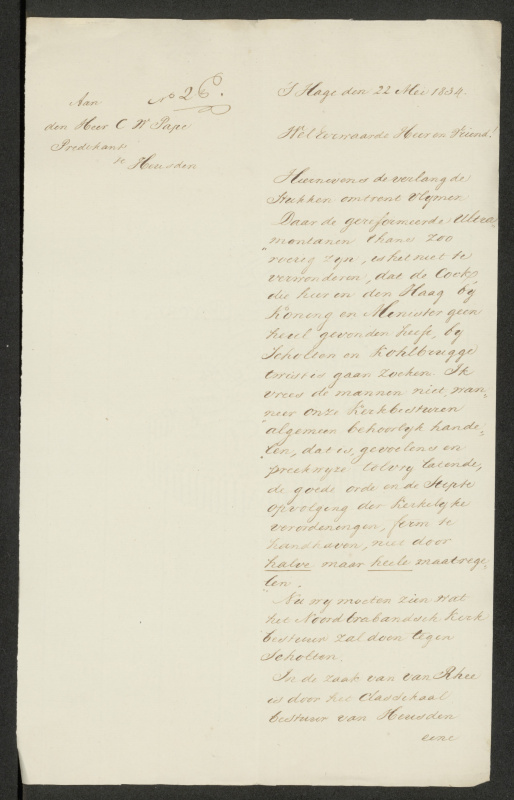

- Letter of Secretary Janssen to Rev. C.W. Pape at Heusden, regarding Hendrik Scholte, 22 May 1834. Written at the time of the Secession, the letter refers to the ecclesiastical procedures in process against Scholte. Janssen also indicates that, “now that the Ultramontanist Reformed are so turbulent,” stringent measures will have to be taken against ministers who refuse to toe the line. National Archives of the Netherlands, coll. 2.07.01.03, Archive of the Department of Reformed and Other Worship, except Roman Catholic, 1815-1870, inv. no. 1555.

- The famous Jaarsma bakery in Pella at work. Photo courtesy of Jessi Vos, Pella Historical Society and Museums.

- Spring street washing in Pella, 6 May 2022. Photo by Andrew Schneider, KNIA/KRLS Radio.

- Tulip Time Parade float. This float is about the story of a reluctant pioneer: Maria Hendrika Elisabeth Scholte, the wife of Hendrik Scholte. Maria did not want to go to the New World and leave her family, the grave of her first baby and her beautiful house in Netherlands. After arriving in Pella she and her husband first lived in a log cabin in what is now Central Park in Pella. The main thing that Maria was looking forward to was the arrival of her collection of Delftware, which was still to be delivered. When it finally arrived, Maria and her maid Dirkje eagerly opened the crates, only to find that very little of her Delftware had survived the journey. Only five plates, it is believed, remained unbroken. Maria was crushed. When the Scholte House, built just across from the log cabin, was finished, Maria made a path of broken Delftware from the doorway of the cabin to the door of her new home. Decades later, Highway 163 (Washington Street), was constructed between the two house and pieces of Delftware were found. Some are now on display in Maria’s Tea Room, on the west side of the Scholte House, the main building of the Pella Historical Society. Hence this float with a crate labeled “Breekbaar,” fragile. Photo by Andrew Schneider, KNIA/KRLS Radio.